- Home

- Masatake Okumiya

Zero Page 2

Zero Read online

Page 2

Several other misconceptions in Zero are based in Horikoshi’s lack of understanding at just what his designs were facing out on the battlefields of the Pacific and East Asia. During the design and development phase of building the Reisen, Horikoshi was operating under the misconception that his new fighter was big (compared with earlier Japanese carrier fighter designs), powered by a huge radial engine, and even fueled by state of the art (for Japan) 93 octane aviation gasoline. In fact, by Western standards of the day, the Zero was light and small, with a tiny radial engine and powered by fuel with much less stored energy than the 100+ octane blended fuels being produced in the United States. So fixed and limited were the tools and technologies he had to work from, that he did not even realize the handicaps he and his fellow Japanese designers had operated under until after the surrender in Tokyo Bay. That the Zero was so dominate early in the Great Pacific War is perhaps his greatest tribute.

In the case of the Type 0 Reisen, these shortcomings showed in details like the lack of self-sealing fuel tanks and armor plating for pilots in planes like the Zero. While comparatively contemporary American aircraft became virtual flying fortresses for their aircrews, Japanese planes frequently became funeral pyres. The lack of protective crew armor meant that aircrew that might have bailed out and lived to fight another day went down with their planes, lost forever to an ever shrinking pool of Japanese naval aviators. This downward spiral would reach a point that by the end of 1944, the Imperial Japanese Navy could not gather enough planes and crews to put air groups onto carriers to oppose the American landings at Leyte in the Philippines. By the end of that great battle general use of kamikaze suicide tactics was in effect and would remain that way until the end of World War II. It is a tragic story, one that you will find documented in amazing detail here in Zero.

I therefore offer to readers, with more than a little pride, the first new American edition of Zero in over a decade. It is presented here pretty much as it was in 1957, with all the pluses and minuses still there for readers to discover and explore for themselves, much as I did. I hope that you get as much out of it as I did when Zero came into my life. Some books can change your perspective and outlook. Zero helped to change my life, gave me insight, shaped my future, and led me down a path that today lets me share it with readers again, some for the very first time. I hope that you will enjoy it as much as I have, and will. And if it provides an insight into the minds of new opponents and challenges for our newly changed future, then Zero will have worked its magic on a new generation once more.

John D. Gresham

Fairfax, Virginia

October, 2001

Preface

On the first day of World War II, the United States lost two thirds of its aircraft in the Pacific theater. The Japanese onslaught against Pearl Harbor effectively eliminated Hawaii as a source of immediate reinforcements for the Philippines. And on those beleaguered islands, enemy attacks rapidly whittled down our remaining air strength until it could no more than annoy a victory-flushed foe.

Japan controlled as much of the vast China mainland as she desired at the time. She captured Guam and Wake. She dispossessed us in the Netherlands East Indies. Singapore fell in humiliating defeat, and brilliantly executed Japanese tactics almost entirely eliminated the British as combatants. Within a few months fearful anxiety gripped Australia; its cities were brought under air attack. Japanese planes swarmed almost uncontested against northern New Guinea, New Ireland, the Admiralties, New Britain, and the Solomons. Enemy occupation of Kavieng, Rabaul, and Bougainville not only threatened the precarious supply lines from the United States, but became potential spring-boards for the invasion of Australia itself.

No one can deny that during those long and dreary months after Pearl Harbor the Japanese humiliated us in the Pacific. We were astonished—fatally so—at the unexpected quality of Japanese equipment. Because we committed the unforgivable error of underestimating a potential enemy, our antiquated planes fell like flies before Japan’s agile Zero fighter.

At no time during these dark months were we able to more than momentarily check the Japanese sweep. The bright sparks of the defenders’ heroism in a sea of defeat were not enough. There could be no doubt that the Japanese had effected a brilliant coup as they opened the war.

It is astonishing to realize, then, that even during this course of events Japan failed to enjoy a real opportunity for ultimate victory. Despite their military successes, within one year of the opening day of war the Japanese no longer held the offensive. The overwhelming numerical superiority which they enjoyed, largely by destruction of our own forces with relative impunity, began to disappear. By the spring of 1943 the balance clearly had shifted. Not only were we regaining the advantage of quantity; we also enjoyed a qualitative superiority in weapons. The Japanese were on the defensive.

The majority of the Japanese military hierarchy could not agree to this concept. They viewed the setbacks in the Pacific as no more than temporary losses. They basked in their successes of the first six months and reveled in a spirit of invincibility. Enhanced by centuries of victorious tradition, cultured by myths and fairy tales, and bolstered by years of one-track education, Japanese confidence of victory was even greater than our own.

There are many reasons why the Japanese failed in their bid to dominate half the world. One reason, it has been said, is that while Japan fought for economic gain, we fought a strategic war of vengeance, a war which promised a terrifying vendetta for the people of Japan.

We can be much more specific than this. The Japanese failed, primarily, because they never understood the meaning of total war. Modern war is the greatest cooperative effort known to man; the Japanese never were able to fuse even their limited resources into this effort. They limped along with a mere fraction of our engineering skill. Throughout the war they were constantly astonished at the feats of our construction crews which hacked airfields out of solid coral and seemingly impenetrable jungle, at the rapidity with which we hurled vast quantities of supplies ashore at invasion beachheads. Air logistics in the form of a continued flow of airborne supplies was unknown to them.

The Japanese lacked the scientific “know how” necessary to meet us on qualitative terms. This was by no means the case early in the war when the Zero fighter airplane effectively swept aside all opposition. In the Zero the Japanese enjoyed the ideal advantage of both qualitative and quantitative superiority. The Japanese fighter was faster than any opposing plane. It outmaneuvered anything in the air. It outclimbed and could fight at greater heights than any plane in all Asia and the Pacific. It had twice the combat range of our standard fighter, the P-40, and it featured the heavy punch of cannon. Zero pilots had cut their combat teeth in China and so enjoyed a great advantage over our own men. Many of the Allied pilots who contested in their own inferior planes the nimble product of Jiro Horikoshi literally flew suicide missions.

This superiority, however, vanished quickly with our introduction of new fighter planes in combat. As the Zeros fell in flames, Japan’s skilled pilots went with them. Japan failed to provide her air forces with replacements sufficiently trained in air tactics to meet successfully our now-veteran airmen who made the most of the high performance of their new Lightnings, Corsairs, and Hellcats.

At war’s end half of all the Japanese fighter planes were essentially the same Zero with which the Japanese fought in China five years before.

In the critical field involving the development of new weapons Japan was practically at a standstill while we were racing ahead. Her few guided missiles were never used in combat. She had in preparation one jet airplane, and that flew but once. Japanese radar was crude. They had nothing which even approximated a B-17 or a B-24—let alone a B-29. And Japan constantly was perplexed and bewildered by a profusion of Allied weapons—air-to-ground rockets, napalm, computing sights, radar-directed guns, proximity fuses, guided missiles, aerial mines, bazookas, flame throwers, and brilliantly execut

ed mass bombing. It was the Japanese inability to counter these weapons, let alone produce them, which had them on the ropes during the last two years of war.

The Japanese failed because their high command made the mistake of believing its own propaganda, to the effect that there was internal dissension in the United States, that we were decadent, that it would require years for us to swing from luxury production to a great war industrial effort. This in itself was a fatal error for, despite the drain of the fight against Germany, even by sheer weight of arms alone we eventually would have overwhelmed an enemy whose production was never ten per cent of our own at its peak.

Japanese strategists and tacticians fought their war entirely out of the rule books. These were never revised until ugly experience taught the Japanese that the books were obsolete, that we were fighting a war all our own—on our terms. The enemy became dumbfounded; they were incapable of effective countermeasures.

The Japanese high command was inordinately fond of the words “impregnable, unsinkable, and invulnerable.” That such conditions are myths was unknown to them.

Their conception of war was built around the word attack. They could not foresee a situation in which they did not have the advantage. Once on the defensive, they threw away their strength in heroic banzai charges where massed firepower slaughtered their ranks. Sometimes when the trend was against them, they lost their capacity for straight thinking and blundered, often with disastrous results.

The Japanese failed because their men and officers were inferior, not in courage, but in the intelligent use of courage. Japanese education, Japanese ancestor worship, and the Japanese caste system were reflected time after time in uninspired leadership and transfixed initiative. In a predicted situation which could be handled in an orthodox manner, the Japanese were always competent and often resourceful. Under the shadow of frustration, however, the obsession of personal honor extinguished ingenuity.

The execution of Japanese plans was totally unequal to the grandiose demands of their strategy. Never was this so true as in the Japanese failure to understand the true meaning of air power. Because they themselves lacked a formula for strategic air power, they overlooked the possibility that it would be used against them and so were unprepared to counter it. Japanese bombers never were capable of sustaining a heavy offensive. To the Japanese, the B-17s and B-24s were formidable opponents; the B-29 was a threat beyond their capacity to counter.

The collapse of Japan brilliantly vindicated the whole strategic concept of the offensive phase of the Pacific War. While ground and sea forces played an indispensable role which can in no sense be underestimated, that strategy, in its broadest terms, was to advance air power to the point where the full fury of crushing air attack could be loosed on Japan itself, with the possibility that such attack would bring about the defeat of Japan without invasion.

There was no invasion.

Japan was vulnerable. Her far-flung supply lines were comparable to delicate arteries nurtured by a bad heart. The value of her captured land masses and the armed forces which defended them was in direct proportion to the ability of her shipping to keep them supplied, to keep the forces mobile, and to bring back to Japan the materials to keep her factories running. Destroy the shipping, and Japan for all practical purposes would be four islands without an empire . . . four islands on which were cities made-to-order for destruction by fire.

Destroy the shipping and burn the cities. We did.

To the submarines goes the chief credit for reducing the Japanese merchant fleet to a point where it was destroyed or useless. Air power also played a great part in this role by sinking ships at sea (the A.A.F. destroyed more than one million tons in 1944) and sealing off Japanese ports with aerial mines.

We burned the cities. The B-29s reaped an incredible harvest of destruction in Japan. Her ability to continue the war collapsed amid the ashes of her scarred and fire-trampled urban centers. The two atomic bombs contributed less than three per cent of the destruction visited upon the industrial centers of Japan. But they gave the Japanese, so preoccupied with saving face, an excuse and a means of ending a futile war with honor intact.

The full story of the vast Pacific war, however, never has been told. It is one thing to study that war from your own viewpoint, but quite another to examine it from that of the enemy.

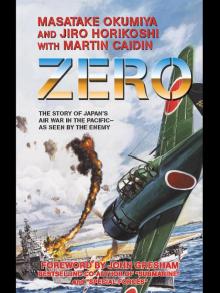

Therein lies the reason for this book. In its entirety, ZERO! is a Japanese story, told by the Japanese. The liberties I have taken in writing this book for the American public do not infringe upon the story of the two Japanese authors. There are instances where I do not agree with Masatake Okumiya and Jiro Horikoshi, but it is their story, not mine, which you will read.

Where readability is aided I have replaced the complicated Japanese aircraft descriptions and designations with terms more familiar to the American reader. For example, the Claude is the Type 96 Carrier Fighter, the Jack is the Raiden fighter plane, the Val is the Aichi Type 99 Carrier-Based Bomber, and so forth. All code names are those employed by U.S. forces in World War II.

Questionable passages and data have been carefully checked against official American histories, and the apparent inconsistencies put before the Japanese for clarification. However, the writer must emphasize again that the sentiments and feelings, the data and reports, are those of the Japanese authors. Every word in this book has been carefully studied by them to produce, from the Japanese point of view, an accurate history and appraisal of the Pacific War. Okumiya and Horikoshi, aided by many of their wartime colleagues, have provided us with a fascinating new perspective of that great conflict.

These Japanese are what I would call “complimentary to their enemies.” In ZERO! they are completely forthright, honest, and prepared to call a spade a spade. While you will read of the humiliating victories of the Japanese over our own forces, you will find equally honest accounts of Japanese defeats and routs—as told by our former enemies. There are no attempts at evasion; there is frank admission of Japanese inadequacies in planning and in fighting.

Both Masatake Okumiya and Jiro Horikoshi are ideally suited to present the Japanese side of the World War II story. Okumiya is a former flying officer of the Japanese Navy with active service and combat flying experience over a period of fifteen years. A graduate of Japan’s Naval Academy, Okumiya as a Commander engaged in most of the major sea-air battles in the Pacific from 1942 to 1944, as a staff officer of carrier task forces. The Midway-Aleutian Sea Battle, the Guadalcanal Campaign, the Santa Cruz Battle in 1942 and the Marianas Campaign in 1944, are only a few. Okumiya was actively engaged in the crippling air campaigns fought in the Solomon Islands and the New Guinea area. For the last year of the war he was placed in command of Japan’s homeland air defense as a staff officer of General Headquarters in Tokyo.

He is considered one of Japan’s leading air-sea strategists, and today holds a high position in the new Japanese Air Force. The combat material in this book is his contribution.

Jiro Horikoshi is considered by his associates as one of the world’s greatest aeronautical engineers and, indeed, is held in the highest esteem in international circles. A graduate of Tokyo Imperial University, he joined the Nagoya Aircraft Works of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd., in 1927, and with that firm served in many engineering and director capacities. From his drafting board emerged several of Japan’s greatest fighter planes, the Claude, the famous Zero, the Raiden, and the spectacular but ill-fated Reppu.

Horikoshi’s contributions to Japan’s aeronautical industry played a great part in enabling that nation to achieve originality of design, to gain her first independence of foreign aeronautical science and products. His engineering background and the vital role played by his design products in China and during World War II, make Jiro Horikoshi’s story a unique and revealing look into a hitherto untold chapter of Japan’s history.

Prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, not all the members of the Japanese high command wished a war with the United States. Especially a

mong the Naval staff were three men with the ability to foresee the dire consequences of such a conflict. More than any other Japanese military officer, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, protested vigorously against the war. He accurately forecast that, if the war continued beyond 1943, Japan was doomed to defeat. But Yamamoto’s warnings, as well as those of other officers and government statesmen, fell on deaf ears. Hideki Tojo committed his ill-equipped nation to a bitter defeat. Isoroku Yamamoto died in air combat in 1943, but his predicted conduct of the war proved astonishingly correct.

It is refreshing not to find in ZERO! the bungled attempts at evasion of responsibility for the war which are so prevalent in the biographies prepared by former members of the German High Command. It is astonishing indeed, to learn that so many German generals and statesmen had absolutely nothing to do with their nation’s preparations for war. With weary familiarity the ex-leaders of Germany “prove” their innocence of participation in the schemes which produced history’s greatest blood bath. You will not find such insultingly naïve passages in this book.

By mid-1943 the Empire of Japan was beaten. There was no longer any question as to the outcome of the war. The peculiarities of the Japanese, however, would not permit any such official admission, even to themselves. And so the war continued, with mounting Japanese casualties, with frenzied suicide attacks, with the incredible savagery of fire bombing which the Japanese brought upon them-selves by their own unwillingness to end a useless struggle.

The defeat of Japan is a story which becomes a monumental tragedy. The question now is not how the Japanese ever accomplished as much as they did in the Pacific, but rather why it took us so long to end that war.

Zero

Zero